Shakespeare Alive

Shakespeare Alive

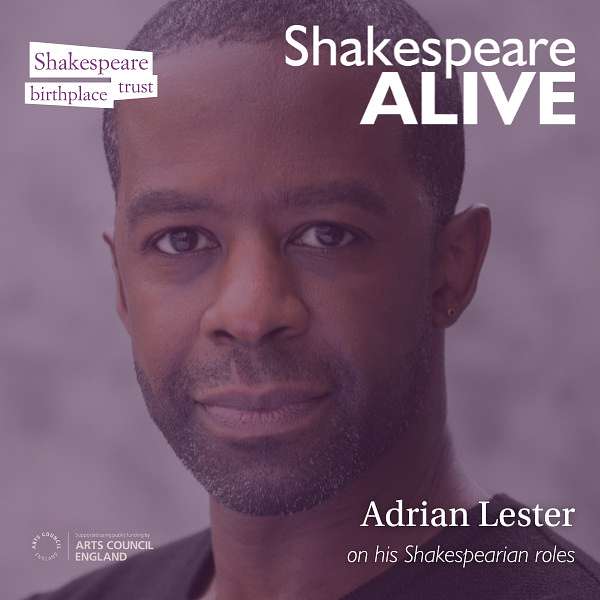

23. Adrian Lester on his Shakesperian Roles

The award-winning actor, Adrian Lester, speaks to Paul about his Shakespearian roles – Rosalind, Henry V, Hamlet, and Othello – working with the late, great director Peter Brook, his portrayal of the pioneering nineteenth-century actor Ira Aldridge, and about why Shakespeare matters.

We ask our guests and listeners to share one modern-day item that they think should be included in an imagined Shakespeare museum of the future. What do you think of their choices, and what would you choose? Let us know at shakespeare.org.uk/future

Paul Edmondson (00:00):

Hello, everybody, and welcome to Shakespeare Alive, a podcast of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. My name's Paul Edmondson. Shakespeare Alive hosts conversations with people who work with Shakespeare throughout the world.

Today's special guest is the actor, Adrian Lester, CBE. He formed part of my earliest Shakespeare theatergoing. His astonishing portrayal of Rosalind in Cheek by Jowl's all-male As You Like It won him the Ian Charleson Award and the Time Out Award. The production came to York Theatre Royal and I went along to see it with my fellow classmates. I travelled to Paris in 2001 to see him play Hamlet for Peter Brook at the Bouffes du Nord. He was a thrilling Henry V for Nicholas Hytner at the National Theatre in 2003. His great Othello there, in 2013, won him and Rory Kinnear, his Iago, the Evening Standard Award. He's portrayed the great 19th century actor, Ira Aldridge, twice in Lolita Chakrabarti's play Red Velvet and he is a singing and dancing Lord Dumaine in Sir Kenneth Branagh's film of Love's Labour's Lost. He's an honorary fellow of the British Shakespeare Association, patron of Birmingham Library's Everything to Everybody project based around their Shakespeare collection and in April this year, he was awarded the prestigious Pragnell prize for a career which has furthered the enjoyment and understanding of Shakespeare. Adrian Lester, welcome to Shakespeare Alive.

Adrian Lester (01:39):

Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Paul Edmondson (01:40):

Like Shakespeare, you were born in the west Midlands-

Adrian Lester (01:43):

Yes.

Paul Edmondson (01:44):

... but what was your route into his works?

Adrian Lester (01:47):

We didn't get taught Shakespeare at school so I didn't come across any of his plays, the plots, the language, anything at all, not reading it round in a classroom, not even in English. We didn't do any drama to speak of. I first encountered Shakespeare... In many ways it was kind of like as an obstacle to getting into drama school. I was a member of the Youth Theatre. I'd heard a few speeches spoken, didn't understand them, and the director of the Youth Theatre, Derek Nicholls, gave me a copy of Measure for Measure and he gave me, at the same time, a Shakespeare glossary and said, "Read it."

But he changed my expectations and, this was the really good thing, he said, "There's a plot that you will understand, which is about a nun and her brother and the guy who's in charge so you'll get that. And there's a whole other plot, that you won't get, which is to do with jokes about words and selling yourself and the underbelly, if you like, of the society. So just get through that but slow down and don't expect to understand everything and use your glossary and use the words like a dictionary, like a key, to help you get through, a code breaker." And I said, "Oh, okay." And so I went very slowly and I read three pages one evening, going backwards and forwards with this book and, remarkably, as I got closer to the end of the play, I didn't need to refer to the glossary because as words came up I thought, "Oh, I know what that means." And I carried on. You sort of understand the language.

Paul Edmondson (03:27):

How old were you at this time?

Adrian Lester (03:29):

I was 16 about to turn 17 and it was also Derek Nicholls' idea that I should audition for drama school a year early, a year too early, because I wouldn't be able to go and then I would be able to go the next year but I'd also know what to expect. And so I auditioned for drama school when I was 17, a year before I'd finished my A-levels, because I knew that I wasn't going to get in and this was just a trial. So it took the pressure off every audition.

I went into every audition just thinking, "What can I get out of this? What's this like? What's the school like? Oh, look, that's how high the ceilings are. Oh, is this how far it is from the tube?" I just went in with that sort of feeling and, funnily enough, that feeling, that lack of pressure, that lack of need, got me two out of my three drama schools. I got two offers. And so I went to RADA but because by the time I arrived at RADA I had just turned 18 but my route into Shakespeare was very, very, very slow, very painstaking approach, and it was Measure for Measure and a production of Romeo and Juliet at the RSC with, it was, Niamh Cusack and Sean Bean and Hugh Quarshi.

Paul Edmondson (04:40):

That was Michael Bogdanov's production.

Adrian Lester (04:42):

Yes. And Michael Kitchen.

Paul Edmondson (04:43):

I think, not long after RADA, 30 years ago, your Rosalind in Cheek by Jowl's As You Like It, from 1991, became famous. Paul Taylor, in The Independent, wrote, "The odds against a strapping, six-foot, Black, male actor being able to create not just a convincing but a captivating Rosalind are, you might have thought, fairly formidable. Adrian Lester makes short work of this assumption in Cheek by Jowl's delightful, all-male As You Like It." What did it mean to you at the time and what has it come to mean to you?

Adrian Lester (05:18):

It began what I feel is a lifelong friendship with the director, Declan Donnellan, who is a genius. It was like a fourth year of drama school. Many people have said that about working with Cheek by Jowl. Declan's approach to acting and truth released and opened up a lot of people.

I first heard about the audition, of course, by my agent who said they wanted me to play Rosalind. And immediately I thought... In this day and age, to have a male Rosalind in a Shakespeare play, it's a wonderful part for a woman. I immediately thought, "Why are we doing that? We shouldn't be doing that." And I had in mind, because it was a comedy and Shakespeare, I had in mind that it was going to be a sort of end-of-the-pier, farcical, running-around-the-forest type thing with the women played by men and I just thought, "Nah, I don't want to be involved in that." And then, typical Declan, just holding true to his ideals, he contacted me again saying would I come and read for Orlando because Declan wasn't sure whether he was going to do a single-sex cast or not. He didn't know, he was just investigating the idea. So I thought, "Okay, he's come back to me and there is no way with a company like Cheek by Jowl you turn them down twice."

So I went along as a young actor and I happily met Declan and we talked about Orlando. We talked about love. I read the speeches. We talked about the nature of desire and external and internal love and all of those things and I came away from that audition thinking, "This guy is brilliant and I want to work with him. And if I get seen for Rosalind as well it might double my chances of being able to be part of the company." So I called my agent and I said, "If they haven't found a Rosalind, please tell him that I'm interested." And I thought that would be the end of it.

But Declan then called me back to audition again, this time for Rosalind, and I read for her. And then I went home hoping I got the part. I went straight back up to continue doing Kiss of the Spider Woman at Coventry's Belgrade Theatre, in the studio. And then I got the note that, yes, I'd gotten the role and in the room we played with notions of gender but we played with the notions of gender only in terms of what they really are which is in how society says you should express the ideas of gender. So, in Japan, it's classically one thing. In Britain, it's classically another. In other countries, it's classically another. They all have their different rules as to if you have a male physique you have to express yourself this way, if you have a female physique you express yourself this way and you wear these kinds of things.

So we decided not to try to pretend to be women, the four guys who were playing the female roles. We didn't want to pretend to be a woman. That was my first mistake, was trying to pretend to be a woman, because I was pretending to be all women and I was concentrating on the physical. As soon as I let go of that, and it took me about two weeks of rehearsal, I think, to let go of that idea that I'm not just portraying womankind on stage, I let go of the physical stuff. So I took away from myself elements that society says were masculine and I took those elements away both in my physical appearance but also in my way of approaching problems. I'd been led to believe men tackle things like this, or they deal with confrontation like this or they... And I had to just unman those, take away those rules that I'd been given.

I decided to play Rosalind specifically her, as the character. It sounds like such a simple thing. And I looked in the mirror and I thought if I was, I pitched her about 17, 18, I thought if I was a 17-year-old woman I would think I was too tall. I would think I was flat-chested. I would think my voice is too deep. I would think, "Oh, my feet are too big." I would think so many crippling things about myself that so many women already naturally think.

And once I got hold of those insecurities, those elements of insecurity, then I found her because, as Declan said in the play, he said, he put it like this, he said, "We want to see a meeting of two people who think they're not worth anything. We want to see a meeting of two people who think they're ugly, they're not worth anything and they've been overlooked by their parents and by their siblings." And when he said that, then, then, then the play opened up and I suddenly understood what Shakespeare had written. And I was really, really happy that I had said yes and wanted to work with him.

Paul Edmondson (10:04):

Well, it's cast a great beam of light across all other productions of As You Like It I've seen since.

Adrian Lester (10:10):

Oh, great.

Paul Edmondson (10:10):

And it's true what people say. You see one great production and then the rest of them just try to measure up.

Adrian Lester (10:17):

Oh, well, great.

Paul Edmondson (10:17):

Well, bless you for your Rosalind. Thank you.

Adrian Lester (10:20):

Oh, she's an amazing woman. She's an amazing woman.

Paul Edmondson (10:23):

What does an actor need to bring with him or her when preparing for and playing a Shakespearean role?

Adrian Lester (10:32):

I think you have to bring with you an understanding that speaking is movement, that there is a power, a physical power, to words, that a clear understanding of what you mean and how you are trying to achieve your goals using nothing but your speech is very, very important. I think it's also important that you have to know, in order to take the energy away from your own body and away from your own face, you have to know what it is you're trying to change. Your words are active. They are tools. They're a screwdriver and a chisel and a machete and sometimes a tiny pin. And they all seek to reshape something, a person, a person's idea of something, an emotion, a thought, even the outside world, even God or trees or nature or the planet, the words are active. And, in that sense, if you join in with how big some of those ideas can be then you join in with the poetry rather than shy away from it.

We can naturalize our Shakespeare. We can do that a lot, and that's great, but we can't neutralize it at the same time. We can do performances where great speeches are turned into a bit of a shrug and that's fine but it's not specific, it's not active. It doesn't change anything. It doesn't ask the right questions because that's what the audience come to see. They pay to see great ideas being pulled apart and reexamined in front of an audience. It's pretty arcane language, fine, we can get over that, but in front of an audience who are themselves already battling with the same ideas.

But we have to understand that when you step out on stage in front of an audience, and this is almost for any play, really, you are pretending to enact something that some member of that audience has truly been through and so, whatever you do, you have to be true to what they know is the truth of their experience. They have to be able to look at you, look at the situation, and find an absolute thread of honesty running through everything that you do on stage because they've been through it themselves, no matter how ridiculous or how terrible the events are.

So even when doing Othello the idea that there's a huge part of Othello's psyche that is hidden from him, that he doesn't truly understand, that when ripped open reveals an unearthly amount of pain, it's almost like a mental breakdown taking place in front of your eyes, there are people in the audience who have had that experience about themselves. And so it's not just a huge poetic aria, an operatic kind of rolling-R kind of big-voiced thing. It is a visceral, immediate, real, important expression of something that we still haven't found the words for yet. That's what Shakespeare does.

Speaker 3 (13:31):

We really appreciate your support for Shakespeare Alive and we'd love to hear from you about how you're enjoying our podcast so please complete our survey by visiting shakespeare.org.uk/future. You can also leave us a review on Apple Podcasts or on your usual podcast platform. Why not join the conversation on social media by using #ShakespeareAlive? And we hope that you enjoy the rest of this episode.

Paul Edmondson (14:03):

I want to recall images of you in my mind, physically, as Hamlet, crouching ready to pounce somehow, slightly feral. Henry V with your troops around you like greyhounds in the slips and that wonderful kind of physical energy. And then I see you in my mind's eye as Othello scouring the bedsheets of Desdemona's bed, your bed, looking for any evidence you can find in that production of an affair. Can you say something about the physical requirements of playing Shakespeare?

Adrian Lester (14:40):

I think with everything I've just said about language, that if you are relaxed and you are free, and you have to be fit as well, I think, but if you're relaxed and you're free then the language does fall into your body and the need to change, the need to be true to the words, means you take on some sort of physical expression of that.

One thing Peter didn't want, when casting his Hamlet, he didn't want what he described as the kind of acting that made him want to leave the country in the first place. He said, "I don't want a sort of inert body with a beautiful voice." He said, "That isn't acting." There is something unquestionably feral about some of the more passionate elements of Shakespeare's work, no matter how well the poetry and the words suit them, there's an element of wildness within them and your body has to be ready. And he didn't want that, he wanted us to be physically very, very, very ready to add movement to the words that we were using. Declan was the same, a lot of movement, a lot of dancing, a lot of play. Nick Hytner was the same. We drilled, we marched, we ran. It was very physical stuff. I have got fit doing Shakespeare, that's one thing that's happened.

Paul Edmondson (16:01):

Tell us a little bit more about working with the late, great Peter Brook. I mean, famously, he asked of Hamlet, "Qui est là? Who's there?" And that was a keynote of the production, wasn't it? Who's there?

Adrian Lester (16:15):

It was. It was. It was who's there as in who's out there and who's there as in who am I? Who's there, speaking to yourself, who's there? Who is it that I'm supposed to be true to?

Hamlet, for me, is the greatest of Shakespeare's plays because the thing that he chooses to change, the thing that he wants to use his words to chisel and hammer at, are ideas, big ideas, of our relationship to fate, our relationship to God, our relationship to our mothers, our fathers, our relationship to family, our relationship to country, all in terms of duty, he has a huge sense of duty. It puts him in a huge area of doubt and doubt is the best place for any character to begin a painful exploration. Othello is placed in doubt. Henry V, even though he's convinced of his ideas at a certain point, the most important point in the play, I think, when he wanders amongst his troops and he speaks about the ideas of duty and service and kingship and so on all wrapped around with doubt, with not knowing which way to go until you investigate everything. That's a brilliant place to be, a brilliant place that Shakespeare always writes from, betrayal and doubt.

With Hamlet, Peter and I began work on our own for a week at his studios and we sat on the floor and I went through the play speaking Hamlet speeches, for meaning, with Peter sat less than a meter away from me just with his eyes closed, listening. And he wanted to be perfectly focused on every word to make sure that we both agreed and I knew what Hamlet was saying or trying to say. And that experience was wonderful. I do that now. When I was doing Othello, when I was doing Red Velvet, I sat down on the floor and just spoke to myself very quietly to make sure that I understood exactly what was being said.

When Peter has a production, when he did have a production, ready to go into, if you like, previews he would take all the actors, no real props, no lighting, no costume, he would take all the actors and get a space at a university college, an international university, normally in Paris or... He wanted a place that spoke English. And in front of students, young people, many of whom don't go to the theater, he wanted to perform the play. And we would perform the play in front of these students and Peter would watch the students. He found them an unfiltered barometer of attention. He found their responses honest, true, without the need for the theatricality behind the theatrical so, in a way, tearing your ticket stubs and buying your drink maybe, and chattering nicely to somebody you've met there and going in and finding your seats and then the hushed silence that takes place. These are all elements of theater that Peter takes as part of a performance and are untrue as much as anything else.

So he just wanted a space where you could see people walk out into a space and begin to speak. And we did that. Then we took questions from all of the students and their reactions were interesting, very, very interesting and Peter took a lot from that and we went back into rehearsal and did some more work on the play. Any preconception that anybody had about the work they were about to see, he wanted to unseat it, remove it, get round it because it's only by gently surprising people that you can really give them a true emotional reaction, take them the wrong way, and he wanted to do that at the beginning of everything he did.

Paul Edmondson (20:11):

You mentioned Red Velvet and your portrayal of the great actor, Ira Aldridge, 1807 to 1867, in Lolita Chakrabarti's play. Can you tell us a bit about that, playing Ira?

Adrian Lester (20:26):

It was a labor of love for me. I know how long Lolita had worked on that piece. I was either beside her or downstairs as she started to do her research. When the internet was in its infancy she was sending faxes to universities and libraries in America and asking for work to come back. She could hardly get any information here but it was all of the scholars, all of the scholars, thank God for the scholars who have their pet projects all around the world because they were the people, even emailing somebody in Poland, they were the people who keep the forgotten ideas and forgotten achievements alive. And she contacted them and she slowly put together so many versions of the play. It took seven years to get it on the theater, seven years, and she sent the play out to, I think, by the time she got it on at The Tricycle, every subsidized theater in London had turned it down, mostly. No one was interested in it.

And at that point I had some sort of standing as an actor in Britain, as a theater actor in Britain, but even then people wouldn't do it, until it got done at The Tricycle, and we pulled all the stops out to make sure it was a fine production. I think it's a very, very important play. She wanted it to speak to more than just the surface area of skin color and people's negative perceptions of that. She wanted to talk about art. She wanted to talk about perception. She wanted to talk about who owns the space in which we say which is good and what's bad. And she has all those discussions. She has characters have all of those discussions on stage. She wanted to talk about women. She wanted to talk about politics. She wanted to talk about Jews in Poland and being sidelined and pushed to one side. And she brought all of that, all of that, to the play.

And what's interesting is I found a few male reviewers completely missed the female element. They absolutely watch the play and there's a powerful, I think, speech toward the end by the reporter character, I won't go into it, but anyway she gives a speech and Ira is making himself up to play King Lear and so many people said that she needed a big speech there so that Ira could do his makeup but what is said in the speech they completely missed.

And then we had one woman who came from Poland who was an actress and she'd come to... Of course, our cousins in Europe speak about five or six languages, we only normally speak one, maybe two. She spoke Polish and German and English and she said that the German at the beginning was wonderful, but she got very, very tearful when she talked about Poland and the fact that no one speaks of Polish history. And she said to see that woman on stage telling the audience about her passions and her dreams, she said she found it incredibly moving and said it was so powerful. I was so grateful that she had come along that night and said that.

But playing him was wonderful. I had to learn, talk about physicality, I had to learn to play in a kind of Georgian, 19th century, Victorian style of theater acting that we don't do anymore and it's almost the style that if you were to say to an actor, "Pretend to do some bad Shakespearean acting," they would do all the things that they used to do in the Victorian era. The actor would suddenly have a big voice and suddenly squat and have wide knees and big gestures and be big with their face and actually that's what those guys did.

So we found ourselves in rehearsal thinking we have to be true to the physical nature of the very, very old style of performance but we have to make that style of performance exciting for a new audience. We have to somehow, in those huge gestures, get our modern audience to understand that this is good acting. That was very, very difficult because within that the actors in the company had to adopt their style and then I had to play Ira's style in the same vein but in a slightly more modern way than they were playing. So I had to work out what they were doing and then slightly modernize it so that they could look down on what Ira was doing. It was very, very delicate and very tricky. Again, it taught me a lesson in that it taught me that big is brilliant as long as it is deeply connected to truth and deeply rooted in reality, you can be as big as you like and it will work.

Paul Edmondson (25:26):

Is there a film version of Red Velvet. Was it recorded in any way? Can we access it?

Adrian Lester (25:32):

I think it was recorded. Yes, it was recorded. We are working on the film of the play so we are hopeful that at some point we'll be able to get a reel set with reel cameras and edit it and have [inaudible 00:25:47].

Paul Edmondson (25:46):

Oh, strength, strength to your elbow on that film. We can't wait to see it.

Adrian Lester (25:50):

Well, we hope, we hope. Fingers crossed.

Paul Edmondson (25:52):

Talking about Shakespeare films, you memorably were a singing and dancing Lord Dumaine in Kenneth Branagh's musical version of Love's Labour's Lost and, indeed, Oliver de Boys in his As You Like It.

Adrian Lester (26:06):

Yeah. Yeah.

Paul Edmondson (26:07):

What's your own favorite Shakespeare film, Adrian, and why?

Adrian Lester (26:12):

I am a massive fan of Baz Luhrmann's Romeo and Juliet because in... And I know now, if I watched it now, I'd cringe at certain points and so that's not fair to do that to a film that reinvented our modern understanding of film language. Film language moves so fast so if you are thinking of directing something you watch everything that's around, you do what you think, what you want to interpret. Once you've done it, give it five, six years and already the ideas that are in your film are already kind of old. It just works that way.

But what he did, the way he invented, reinvented, even down to having the guns called Swords, so that the make of the guns they were using was a Sword 99 or a Sword 5.4 or a Sword pump action so that, "Put up your Swords," and so on and even that worked for me, that gangland sort of lawless area full of partying and drugs and irreverence and the two most powerful people being these two families. I thought it was wonderful. And then the moment when, I think it's DiCaprio and Claire Danes, they see each other at the party and there's a fish tank and they're so young and open and vulnerable and... Yeah, I really liked that film. When I saw it I was amazed that someone could make Shakespeare so exciting and powerful and playful and so on. And then I saw the Zeffirelli production of Romeo and Juliet which is very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very traditional and it's all the same language and I thought, "Wow. What Luhrmann did was amazing."

Paul Edmondson (28:08):

Well, I'm going to go and see it again. I saw it at the cinema and loved it but it's years since I've seen it.

Adrian Lester (28:13):

It's years and it may not stand up, it may not, I warn you.

Paul Edmondson (28:16):

Well, well, we'll see, but it was lovely to hear you talking about it. You are patron of the Everything to Everybody project which brings to the fore Birmingham Library's important Shakespeare collection but closer to my home, as it were, Stratford-upon-Avon, if you were to deposit something in the library, archives or museum collection of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, what would you deposit and why?

Adrian Lester (28:42):

I began, of course, thinking about a prop or a book or a particular film or a something that people could sort of go, "Oh, this is a prop from the 1964 film of..." blah, or, "This is a book from..." or, "This is someone's notes from..." so and so. I actually have Peter Brook's copy of Hamlet with all of his notes in the margin, which I got a hold of. Something like that, you go, "Oh, this is..."

But the continuation of the appreciation of Shakespeare, if I can put those two words together in the same sentence, is something that is important to me and I think what would be great in the archives is if we, and this is something I think we should do, we should go visit some great actors, some great writers who love and appreciate Shakespeare and we should ask them why and if they had to tell a future generation something that was important about Shakespeare, what would it be? And we should take all of those interviews, we should take all of the things they say, edit them down, put them on a half-hour film and when people walk into the library that film is playing on a loop and you can pick up your headphones and put them on and listen to people express ideas about a writer that you may not have come to understand yet or you might want to discover later or that you know yourself and have them reaffirmed. That is something we should do, I think, at the library.

Paul Edmondson (30:23):

Well, I think we need that in the Birthplace itself as hundreds of thousands of people pass through it. That's an astonishing thought, thank you. And thank you, Adrian, for this inspiring conversation.

Adrian Lester (30:35):

You're welcome.

Paul Edmondson (30:36):

I mean, I've seen you play the roles you've been talking about but hearing you talk about Shakespeare and your career and your close connection to his words and thoughts and ideas has been just wonderful. Adrian Lester, thank you very much indeed for joining us on Shakespeare Alive.

Adrian Lester (30:54):

Thank you very much. Thanks for having me.

Speaker 3 (30:57):

Thank you for listening to this episode of Shakespeare Alive with Paul. Join me next week when I speak to actor Freddie Fox about his journey with Shakespeare. If you'd like to find out more about the houses, collections, research and education activity at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust then please head over to our website, shakespeare.org.uk